2013

Open Access

20/11/13 10:02

I’ve got a thing in the back of my mind now that it is time to change how I submit manuscripts. There is a growing pressure to consider submission of pre-prints, with the most complete arguments I’ve read being made by John Bruno and Jon Wilkins, two scientists I respect for far more than their names. I have little interest in adding another step to the process of making my science publicly known via publishing. However, there are some factors where pre-publication, in appropriate online archives including PeerJ and bioRxiv, certainly makes sense.

The cost of publishing science has never been negligible, but now that we are asked (and it makes sense) to publish in open-access journals so that all citizens of the nations that fund our work can read it, we are often faced with $1500-2000 fees to publish in permanent ways on online servers. However, some (not all) journals will allow you to publish after submitting a version of a manuscript to a pre-print server, and then will allow you to archive the final version on that publicly-accessible server after a short period of time. This could cut the cost of open access considerably.

It also makes sense to me that this could be a ripe opportunity to gain additional input into appropriate analysis and interpretation of data, beyond the typical friendly peer review we all go through. I’m skeptical on this point, as I don’t think my publications on open access journals such as PLoS ONE have garnered much comment in the years they have been up. However, it is possible.

The question will be, and I will test the waters soon, what is requested or required for submission? It doesn’t have to go through peer review, but what formatting and other steps are necessary? How many of these steps are ultimately necessary for publication anyway (and thus just egg along the process)?

The other problem of course is the potential for further dilution of what is branded ‘peer-reviewed’ science. John Bruno, linked above, makes some good arguments that the peer-review system is deeply flawed, and it is. However, it is the only gatekeeper we have when those that are trying to sow doubt about evolution and climate change attempt to fraudulently influence the public understanding. A difficult tension between the two goals: widespread dissemination, and authority. Hmmmm.

The cost of publishing science has never been negligible, but now that we are asked (and it makes sense) to publish in open-access journals so that all citizens of the nations that fund our work can read it, we are often faced with $1500-2000 fees to publish in permanent ways on online servers. However, some (not all) journals will allow you to publish after submitting a version of a manuscript to a pre-print server, and then will allow you to archive the final version on that publicly-accessible server after a short period of time. This could cut the cost of open access considerably.

It also makes sense to me that this could be a ripe opportunity to gain additional input into appropriate analysis and interpretation of data, beyond the typical friendly peer review we all go through. I’m skeptical on this point, as I don’t think my publications on open access journals such as PLoS ONE have garnered much comment in the years they have been up. However, it is possible.

The question will be, and I will test the waters soon, what is requested or required for submission? It doesn’t have to go through peer review, but what formatting and other steps are necessary? How many of these steps are ultimately necessary for publication anyway (and thus just egg along the process)?

The other problem of course is the potential for further dilution of what is branded ‘peer-reviewed’ science. John Bruno, linked above, makes some good arguments that the peer-review system is deeply flawed, and it is. However, it is the only gatekeeper we have when those that are trying to sow doubt about evolution and climate change attempt to fraudulently influence the public understanding. A difficult tension between the two goals: widespread dissemination, and authority. Hmmmm.

Cost of Data

13/11/13 12:09

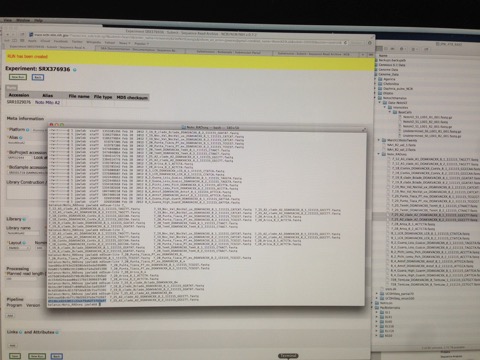

Data are fun, but cost lots of money up front - I just maxed out my purchasing card today - and cost lots of time when you have to curate them to NCBI. Pleeeeeeeease somebody come up with a better way to post data to Genbank, pretty please?

Less is More

28/10/13 11:51

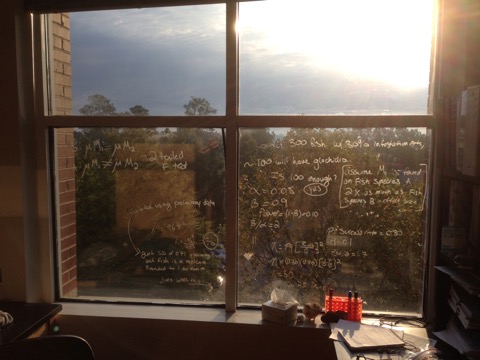

Everybody in the Genetics Department gets effectively the same 1000 sq ft lab to start with. They are functional but charmless - that is, they are functional if you are cloning and doing a lot of bench-top science. For bioinformatics, animal rearing, etc. the labs are less well planned, and if you actually want to talk to people in the lab without ducking under and around the shelving it gets awkward. So my renovations, maintaining all the potential for using the lab benches as they have traditionally been used but opening space up for our computational environment, have begun. We are capping all the water/gas/vacuum on this bench, having new outlets installed, and eliminating the sinks. Everybody is excited about it, and I think it will do a lot for the overall feel and ethos of the lab. We don’t do traditional bench-top genetics. I figure I’ll be in this lab for another 20 years, perhaps, so I may as well like it.

(wrong picture somehow ended up here previously)

(wrong picture somehow ended up here previously)I am adding this update a couple weeks later because it is the same basic topic. I love that my lab is not merely/primarily a place of getting things done, but a place of learning and interaction. Inspired by what I’ve heard of the Santa Fe Institute, I encouraged my folks a few years back to use their windows to best advantage. We play music, we stop to talk about ideas, we have a constant supply of scrap paper to explain something to another colleague or student. That’s the way it is supposed to be. I can’t take any individual science project going on in my lab too seriously: they are barnacles, they are mussels, and so on. But the overall pursuit of understanding is a pretty beautiful thing some days.

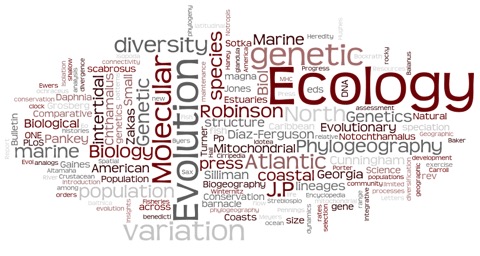

Molecular Ecology

06/10/13 10:37

That is just me fooling around with what words fall out of my CV. I guess I work on evolutionary ecology. Or molecular ecology. Or molecular evolution. No surprise there.

All I really know right now is that teaching these subjects is hard. I’m completely focused on writing lectures and writing exams and figuring out grading schemes and trying to be fair but challenging and interesting…..I’m exhausted. I gave a terrible exam yesterday - too long, or too difficult, I haven’t yet determined. But that erodes a lot of confidence that I was trying to build up with the students in evolutionary biology. That along with a string of days in which there is a committee meeting every day, a (successful and good) qualifying exam for Wares lab member Katie Bockrath, dissertation defense yesterday….’tis the season for meetings and examinations, I guess.

Anyway I’m just recognizing that I wish I had the right answers to how to handle all these things, but a lot of the time I don’t.

Green Porno

31/07/13 12:32

OK, maybe every single segment in Isabella Rossellini’s series “Green Porno” isn’t 100% accurate to detail… but it gets close enough for most people.

The whole series is interesting (you may click around on YouTube, but more is available on the Sundance Channel website), and probably more graphic than most people are used to seeing on an academic website - and yet this is, in a nutshell, what we study. Who mates with who, and how, and how often, and when. What they eat is for the ecologists; genetics is, after all, a study of what happens when organisms reproduce.

The whole series is interesting (you may click around on YouTube, but more is available on the Sundance Channel website), and probably more graphic than most people are used to seeing on an academic website - and yet this is, in a nutshell, what we study. Who mates with who, and how, and how often, and when. What they eat is for the ecologists; genetics is, after all, a study of what happens when organisms reproduce.

GenBank

18/07/13 12:44

The GenBank release notes for release 162.0 (October 2007) state that "from 1982 to the present, the number of bases in GenBank has doubled approximately every 18 months.

That is taken directly from Wikipedia today. There are billions and billions of nucleotides in there; probably billions of individual sequences and sequence fragments, plus all sorts of other data. So the question is, how did so much data get uploaded to Genbank when the main data entry portal to Genbank - the program Sequin - is so clunky and flawed?

Current options for uploading data include Sequin, which the last time I used it kept shifting coding sequences around on the mitochondrial genomes I was uploading; tbl2asn which requires that you are familiar with shell scripting, able to generate a tab-delimited data file that has a unique format almost impossible to generate automatically from the spreadsheet or .csv output from other programs; or Geneious, which so far has failed me in that it changes the genetic code from what is annotated in the software.

Yet somehow all these data are there. Most of them missing critical meta-data, like the latitude/longitude from which the sequence came, or who identified the specimen. That takes extra work, and NCBI doesn’t make it easy.

So how can we make this easier? For single-gene submissions, tbl2asn can be very easy because you can annotate most of the data as part of a FASTA file. But we are moving beyond the world of single-gene submissions very quickly. The complication of exons, introns, reverse-strand coded sequences, whole chromosomes, whole genomes means we all need to get more savvy about how to do this.

I don’t have the answer, I’m just complaining. I’m pretty computer/bioinformatics-savvy, so if I find this frustrating what about people who are new to the field?

That is taken directly from Wikipedia today. There are billions and billions of nucleotides in there; probably billions of individual sequences and sequence fragments, plus all sorts of other data. So the question is, how did so much data get uploaded to Genbank when the main data entry portal to Genbank - the program Sequin - is so clunky and flawed?

Current options for uploading data include Sequin, which the last time I used it kept shifting coding sequences around on the mitochondrial genomes I was uploading; tbl2asn which requires that you are familiar with shell scripting, able to generate a tab-delimited data file that has a unique format almost impossible to generate automatically from the spreadsheet or .csv output from other programs; or Geneious, which so far has failed me in that it changes the genetic code from what is annotated in the software.

Yet somehow all these data are there. Most of them missing critical meta-data, like the latitude/longitude from which the sequence came, or who identified the specimen. That takes extra work, and NCBI doesn’t make it easy.

So how can we make this easier? For single-gene submissions, tbl2asn can be very easy because you can annotate most of the data as part of a FASTA file. But we are moving beyond the world of single-gene submissions very quickly. The complication of exons, introns, reverse-strand coded sequences, whole chromosomes, whole genomes means we all need to get more savvy about how to do this.

I don’t have the answer, I’m just complaining. I’m pretty computer/bioinformatics-savvy, so if I find this frustrating what about people who are new to the field?

Yellowfins or Greenheads?

10/07/13 10:32

Mark Scott of SC DNR just posted this to YouTube and I wanted to give it a shout-out.

http://youtu.be/2vJoEraw4QY

Very nice underwater footage of the Middle Saluda River, in the Santee Basin of South Carolina. Whenever you drive over a bridge and look down at the brown waters of southern rivers, don’t think for a minute there isn’t a really interesting aquatic world beneath the surface!

The shiners are labeled green head shiners in this video, Notropis chlorocephalus. Until very recently they were considered part of the yellowfins that I have worked on (N. lutipinnis), but Mollie Cashner has been doing phenotypic and genetic work to show that there is more going on in terms of the history of these fish and these drainages.

http://youtu.be/2vJoEraw4QY

Very nice underwater footage of the Middle Saluda River, in the Santee Basin of South Carolina. Whenever you drive over a bridge and look down at the brown waters of southern rivers, don’t think for a minute there isn’t a really interesting aquatic world beneath the surface!

The shiners are labeled green head shiners in this video, Notropis chlorocephalus. Until very recently they were considered part of the yellowfins that I have worked on (N. lutipinnis), but Mollie Cashner has been doing phenotypic and genetic work to show that there is more going on in terms of the history of these fish and these drainages.

Evolution 2013

01/07/13 12:12

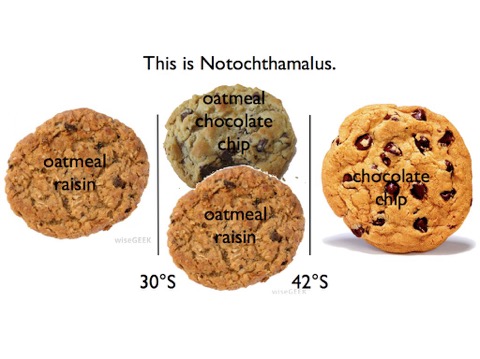

Just back from Snowbird, UT where I presented some of our work on the genetic cline in Notochthamalus, I attach a PDF of the talk for those who might be interested. Chances are good the only person who is really looking is my mom.

PresentationSSE2013

PresentationSSE2013

Barnacles

03/06/13 16:16

Origin of the name [edit]

In 13th-century England the word "barnacle" was used for a species of waterfowl, the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis). This bird breeds in the Arctic but winters in the British Isles so its nests and eggs were never seen by the British. It was thought at the time that the gooseneck barnacles that wash up occasionally on the shore had spontaneously generated from the rotting wood to which they were attached, and that the geese might be generated similarly. Credence to the idea was provided by the tuft of brown cirri that protruded from the capitulum of the crustaceans which resembled the down of an unhatched gosling. Popular belief linked the two species and a writer in 1678 wrote "multitudes of little Shells; having within them little Birds perfectly shap'd, supposed to be Barnacles [by which he meant barnacle geese]."[5]

From Wikipedia entry on Lepas anatifera.

In 13th-century England the word "barnacle" was used for a species of waterfowl, the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis). This bird breeds in the Arctic but winters in the British Isles so its nests and eggs were never seen by the British. It was thought at the time that the gooseneck barnacles that wash up occasionally on the shore had spontaneously generated from the rotting wood to which they were attached, and that the geese might be generated similarly. Credence to the idea was provided by the tuft of brown cirri that protruded from the capitulum of the crustaceans which resembled the down of an unhatched gosling. Popular belief linked the two species and a writer in 1678 wrote "multitudes of little Shells; having within them little Birds perfectly shap'd, supposed to be Barnacles [by which he meant barnacle geese]."[5]

From Wikipedia entry on Lepas anatifera.

Swimming in Data

03/06/13 11:46

In the past 30 days, I have had data from hundreds of SNPs in hundreds of individuals scored, an Illumina Mi-Seq run for the barnacle Chelonibia, same for the coral Agaricia, 24 cells of Pac Bio data in Serratia, 454 data from the Dry Tortugas, and Hi-Seq data for the barnacle Notochthamalus dropped in my lap. I mean lab. We are talking about something like 15 billion nucleotides that I am in theory learning something from. And don’t forget, I am not really a power user of such data!

What is interesting about this problem is only secondarily biology. At this point, learning how to handle such information is one of the biggest challenges science is grappling with. It remains difficult to upload even simple data sets to NCBI (I have hired an IOB graduate student for the year, and his first task is handling submission of some mitochondrial genomes - only 8 15kb fragments - to Genbank, which will probably take him all day). We run out of disk space on our computers on a regular basis, and I will soon have a room full of terabyte drives that are just sitting around to back up the big data files.

At the same time, publishing is stuck in a centuries-old model. Peer review is important, but we are sending more and more submissions out into an ever-expanding galaxy of scientific journals (of varying credibility), to the extent that we actually know less and less about what has been done. It is simply too big. Too much.

It is with that idea that I am so enthusiastically behind wiki technology to combine and compile and collectively edit what we know. Wikipedia is, to my mind, an enormously successful venture. No, nothing is 100% right. But that is equally true for any creation of man. And as it turns out, it is as close to right as any other respected outlet of information.

Not all information, of course, is easily put into a narrative. Nor do we always need a narrative about every bit of news or data. So I was interested to come across Wikigenes, a repository for information on gene regions that allows the collaborative contribution (and credit to be given, for those of us who rely on our CV for promotion, etc.) to this body of information. I haven’t contributed yet - I do contribute sometimes to Wikipedia - but I will definitely consider it as another product of my research.

What is interesting about this problem is only secondarily biology. At this point, learning how to handle such information is one of the biggest challenges science is grappling with. It remains difficult to upload even simple data sets to NCBI (I have hired an IOB graduate student for the year, and his first task is handling submission of some mitochondrial genomes - only 8 15kb fragments - to Genbank, which will probably take him all day). We run out of disk space on our computers on a regular basis, and I will soon have a room full of terabyte drives that are just sitting around to back up the big data files.

At the same time, publishing is stuck in a centuries-old model. Peer review is important, but we are sending more and more submissions out into an ever-expanding galaxy of scientific journals (of varying credibility), to the extent that we actually know less and less about what has been done. It is simply too big. Too much.

It is with that idea that I am so enthusiastically behind wiki technology to combine and compile and collectively edit what we know. Wikipedia is, to my mind, an enormously successful venture. No, nothing is 100% right. But that is equally true for any creation of man. And as it turns out, it is as close to right as any other respected outlet of information.

Not all information, of course, is easily put into a narrative. Nor do we always need a narrative about every bit of news or data. So I was interested to come across Wikigenes, a repository for information on gene regions that allows the collaborative contribution (and credit to be given, for those of us who rely on our CV for promotion, etc.) to this body of information. I haven’t contributed yet - I do contribute sometimes to Wikipedia - but I will definitely consider it as another product of my research.

Now That is a Truck

27/05/13 12:49

The next time we head out for field work in southern Chile, I plan to avoid getting another Kia Gran Vitara. Though it sufficed, I think THIS might really work for us. Though then we wouldn’t have gotten to stay in those beautiful palafitos in Chiloé….

versus….

versus….

Quammen

27/05/13 12:37

If you are even a little bit interested in the travails of 19th-century naturalists and want to know more about the field of biogeography and what it can say about the current extinction crisis our planet is in, I highly recommend David Quammen’s The Song of the Dodo. A phenomenal book on diversity, conservation, biogeography, and evolution. The experience and wisdom involved in writing this book is enviable.

Fecundity 5

24/04/13 12:19

Hard-working Ecology graduate student Meredith Meyers became the fifth Ph.D. to finish up work in my lab. Jim Porter and I co-advised Meredith, meaning she covered a huge breadth of knowledge from coral reef monitoring to barnacle speciation in her time here. She already has two papers out from her time in my lab and another one or two to come. Congratulations Meredith!

Blah blah blah

19/04/13 12:38

A QuickTime video of John Wares' April 17, 2013 seminar is available for viewing on-line via a link at the following URL:

http://www.genetics.uga.edu/Genetics_Seminar_Video-John_Wares.html

http://www.genetics.uga.edu/Genetics_Seminar_Video-John_Wares.html

The Shad Mussel Connection

11/04/13 14:47

I wanted to post this link that showed up on Facebook today regarding the work that Katie Bockrath did to help identify the fish using freshwater mussels as egg habitats - a completely novel observation of this behavior in North American fishes. while the genetics is these days pretty straightforward, natural resources managers are very intrigued about this discovery!

Mic Went Quiet

03/04/13 14:40

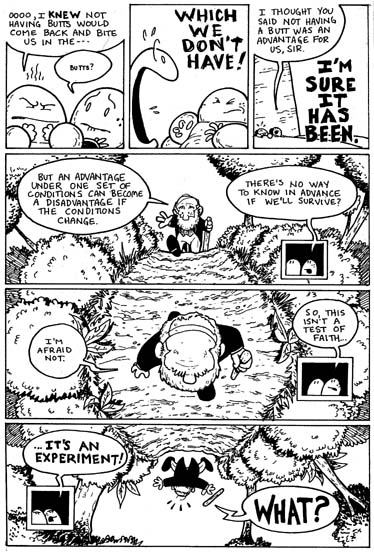

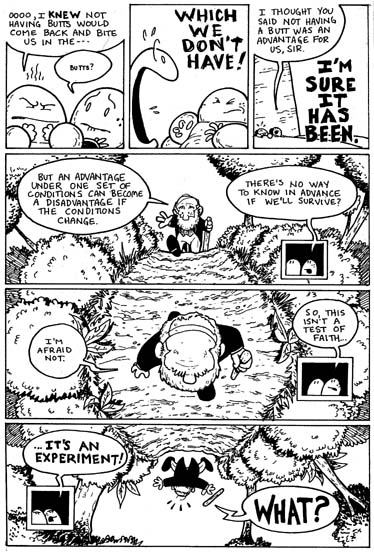

I’m not sure why it has been so long since I added to this... oh, right, two and a half weeks traveling in Chile, and a bunch of administrative tasks to clean up afterwards. I wanted to add a few things, though. First, while I was away (sadly) my evolution-comic-book-hero colleague Jay Hosler came to UGA to talk about his work; the presentation (including my remote introduction) is available here and if you aren’t already familiar with Jay’s work I highly recommend starting with Sandwalk Adventures!

Beyond that, we have been collecting data on the Chilean barnacle cline and two fairly shocking things have come up. First, it is now clear that our hypothesis (that justified the travel to northern Patagonia in the first place) was totally correct: the 42° biogeographic break is of first-order importance for the pattern of mitochondrial diversity in Notochthamalus. Second, the two lineages of Notochthamalus... well, they are basically two species.

This latter understanding comes from some medium-throughput SNP genotyping we have done this spring, and analysis of those genotypes suggests that most individuals have a nuclear background consistent with the far north, or the far south, with little hybridization or introgression. More details to come soon, but this result is a bit of a downer. I had thought we were going to be chasing interesting patterns of cytonuclear disequilibrium and considering incipient speciation or the first steps toward speciation, or just a strong selection-driven cline. Instead, it is just high-tech biogeography, in a sense. It will still be cool, we have big plans for the paper. It is just not what I expected, and of course attachment is the cause of much suffering, in a Buddhist sense!

Beyond that, we have been collecting data on the Chilean barnacle cline and two fairly shocking things have come up. First, it is now clear that our hypothesis (that justified the travel to northern Patagonia in the first place) was totally correct: the 42° biogeographic break is of first-order importance for the pattern of mitochondrial diversity in Notochthamalus. Second, the two lineages of Notochthamalus... well, they are basically two species.

This latter understanding comes from some medium-throughput SNP genotyping we have done this spring, and analysis of those genotypes suggests that most individuals have a nuclear background consistent with the far north, or the far south, with little hybridization or introgression. More details to come soon, but this result is a bit of a downer. I had thought we were going to be chasing interesting patterns of cytonuclear disequilibrium and considering incipient speciation or the first steps toward speciation, or just a strong selection-driven cline. Instead, it is just high-tech biogeography, in a sense. It will still be cool, we have big plans for the paper. It is just not what I expected, and of course attachment is the cause of much suffering, in a Buddhist sense!

Explanations

01/02/13 09:36

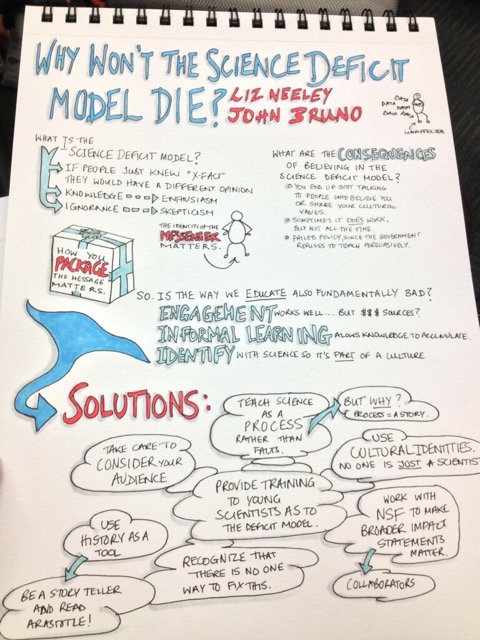

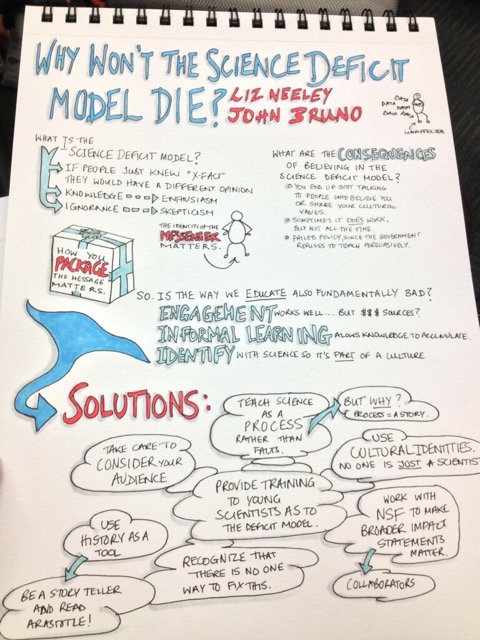

I saw this post from John Bruno (from the Science Online meeting) yesterday and had to share it. There is no reason we should still be having the same discussions over and over and over and over and over. It is clear that just spouting data at people does not work to educate them; as educators, and communicators, we have to figure out better how to resonate with people.

Field Work

11/01/13 09:30

We are preparing for our trip to Chile - my student Christine, her partner Daniel as field crew, and I - and I know this is going to be a good trip. We need to go down there to explore a second genealogical transition in the barnacle Notochthamalus scabrosus, which I’ve been studying for 6-7 years now. It is a good use of my research funds, but one could argue that all three of us don’t need to be down there to scrape barnacles! However, I know the system and have been down there before; it is Christine’s current research; Daniel is more fluent in Spanish and a more experienced field researcher; and we want the project to succeed. But beyond that I had forgotten an important reason to get down there: working with the organisms in the field changes everything about what you know about a biological system.

I just finished re-reading Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez and two passages have to be shared.

“We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, first, by the collective pressure....of our time and race, second ...by our personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes - we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality. The oneness of these two might take its contribution from both. For example: the Mexican sierra has "XVII-15-IX" spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational externality has come into being - an entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth "D. XVII-15-IX." There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailed - probably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.”

and then...

“Our own interest lay in relationships of animal to animal. If one observes in this relational sense, it seems apparent that species are only commas in a sentence, that each species is at once the point and the base of a pyramid, that all life is relational to the point where an Einsteinian relativity seems to emerge. And then not only the meaning but the feeling about species grows misty. One merges into another, groups melt into ecological groups until the time when what we know as life meets and enters what we think of as non-life: barnacle and rock, rock and earth, earth and tree, tree and rain and air. And the units nestle into the whole and are inseparable from it. Then one can come back to the microscope and the tide pool and the aquarium. But the little animals are found to be changed, no longer set apart and alone. And it is a strange thing that most of the feeling we call religious, most of the mystical outcrying which is one of the most prized and used and desired reactions of our species, is really the understanding and the attempt to say that man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known and unknowable. This is a simple thing to say, but the profound feeling of it made a Jesus, a St. Augustine, a St. Francis, a Roger Bacon, a Charles Darwin, and an Einstein. Each of them in his own tempo and with his own voice discovered and reaffirmed with astonishment the knowledge that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things - plankton, a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

And so, we go to the field next month.

I just finished re-reading Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez and two passages have to be shared.

“We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, first, by the collective pressure....of our time and race, second ...by our personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes - we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality. The oneness of these two might take its contribution from both. For example: the Mexican sierra has "XVII-15-IX" spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational externality has come into being - an entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth "D. XVII-15-IX." There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailed - probably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.”

and then...

“Our own interest lay in relationships of animal to animal. If one observes in this relational sense, it seems apparent that species are only commas in a sentence, that each species is at once the point and the base of a pyramid, that all life is relational to the point where an Einsteinian relativity seems to emerge. And then not only the meaning but the feeling about species grows misty. One merges into another, groups melt into ecological groups until the time when what we know as life meets and enters what we think of as non-life: barnacle and rock, rock and earth, earth and tree, tree and rain and air. And the units nestle into the whole and are inseparable from it. Then one can come back to the microscope and the tide pool and the aquarium. But the little animals are found to be changed, no longer set apart and alone. And it is a strange thing that most of the feeling we call religious, most of the mystical outcrying which is one of the most prized and used and desired reactions of our species, is really the understanding and the attempt to say that man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known and unknowable. This is a simple thing to say, but the profound feeling of it made a Jesus, a St. Augustine, a St. Francis, a Roger Bacon, a Charles Darwin, and an Einstein. Each of them in his own tempo and with his own voice discovered and reaffirmed with astonishment the knowledge that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things - plankton, a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

And so, we go to the field next month.