chile

Now That is a Truck

27/05/13 12:49

The next time we head out for field work in southern Chile, I plan to avoid getting another Kia Gran Vitara. Though it sufficed, I think THIS might really work for us. Though then we wouldn’t have gotten to stay in those beautiful palafitos in Chiloé….

versus….

versus….

Field Work

11/01/13 09:30

We are preparing for our trip to Chile - my student Christine, her partner Daniel as field crew, and I - and I know this is going to be a good trip. We need to go down there to explore a second genealogical transition in the barnacle Notochthamalus scabrosus, which I’ve been studying for 6-7 years now. It is a good use of my research funds, but one could argue that all three of us don’t need to be down there to scrape barnacles! However, I know the system and have been down there before; it is Christine’s current research; Daniel is more fluent in Spanish and a more experienced field researcher; and we want the project to succeed. But beyond that I had forgotten an important reason to get down there: working with the organisms in the field changes everything about what you know about a biological system.

I just finished re-reading Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez and two passages have to be shared.

“We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, first, by the collective pressure....of our time and race, second ...by our personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes - we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality. The oneness of these two might take its contribution from both. For example: the Mexican sierra has "XVII-15-IX" spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational externality has come into being - an entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth "D. XVII-15-IX." There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailed - probably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.”

and then...

“Our own interest lay in relationships of animal to animal. If one observes in this relational sense, it seems apparent that species are only commas in a sentence, that each species is at once the point and the base of a pyramid, that all life is relational to the point where an Einsteinian relativity seems to emerge. And then not only the meaning but the feeling about species grows misty. One merges into another, groups melt into ecological groups until the time when what we know as life meets and enters what we think of as non-life: barnacle and rock, rock and earth, earth and tree, tree and rain and air. And the units nestle into the whole and are inseparable from it. Then one can come back to the microscope and the tide pool and the aquarium. But the little animals are found to be changed, no longer set apart and alone. And it is a strange thing that most of the feeling we call religious, most of the mystical outcrying which is one of the most prized and used and desired reactions of our species, is really the understanding and the attempt to say that man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known and unknowable. This is a simple thing to say, but the profound feeling of it made a Jesus, a St. Augustine, a St. Francis, a Roger Bacon, a Charles Darwin, and an Einstein. Each of them in his own tempo and with his own voice discovered and reaffirmed with astonishment the knowledge that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things - plankton, a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

And so, we go to the field next month.

I just finished re-reading Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez and two passages have to be shared.

“We knew that what we would see and record and construct would be warped, first, by the collective pressure....of our time and race, second ...by our personalities. But knowing this, we might not fall into too many holes - we might maintain some balance between our warp and the separate thing, the external reality. The oneness of these two might take its contribution from both. For example: the Mexican sierra has "XVII-15-IX" spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational externality has come into being - an entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth "D. XVII-15-IX." There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailed - probably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.”

and then...

“Our own interest lay in relationships of animal to animal. If one observes in this relational sense, it seems apparent that species are only commas in a sentence, that each species is at once the point and the base of a pyramid, that all life is relational to the point where an Einsteinian relativity seems to emerge. And then not only the meaning but the feeling about species grows misty. One merges into another, groups melt into ecological groups until the time when what we know as life meets and enters what we think of as non-life: barnacle and rock, rock and earth, earth and tree, tree and rain and air. And the units nestle into the whole and are inseparable from it. Then one can come back to the microscope and the tide pool and the aquarium. But the little animals are found to be changed, no longer set apart and alone. And it is a strange thing that most of the feeling we call religious, most of the mystical outcrying which is one of the most prized and used and desired reactions of our species, is really the understanding and the attempt to say that man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known and unknowable. This is a simple thing to say, but the profound feeling of it made a Jesus, a St. Augustine, a St. Francis, a Roger Bacon, a Charles Darwin, and an Einstein. Each of them in his own tempo and with his own voice discovered and reaffirmed with astonishment the knowledge that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things - plankton, a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

And so, we go to the field next month.

Answers Lead to Questions

10/02/11 09:30

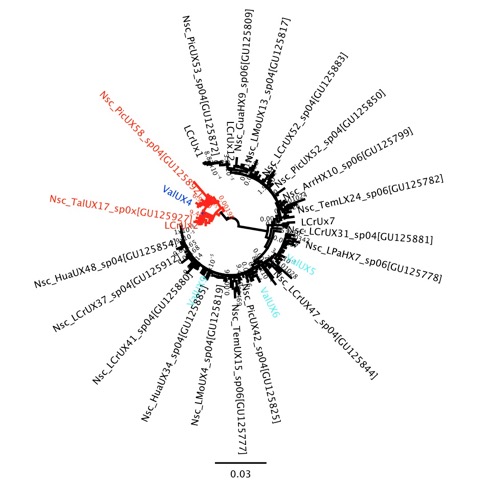

There is nothing too clear about the figure I’ve pasted in here, that is partly intentional because I’m still figuring some things out. But, this figure represents the first new step in understanding the genetic/species patterns along the coast of Chile that my lab has taken since our paper (Zakas et al. 2009) came out in MEPS. New lab technician Kelly Laughlin has been coming up to speed very quickly over the past 4 weeks, and the first sequence data she collected included about 24 individuals of Notochthamalus from near Valdivia, Chile. This is about 500km further south than our survey in the past, and I wondered if the genetic cline that we observed would go to fixation for the southern haplogroup. In the image above, the southern haplogroup is red, the northern haplogroup is black, and in blue (only a small number are shown because of the scale of the tree) are individuals from Valdivia (6 in the red clade, 12 in the black). What this tells me is that the relative B/A frequency in Valdivia is exactly the same (about 1/3) as at Pichilemu, Las Cruces, and Punta Talca far to the north.

This suggests that all of the focus can return to the area around 31°S latitude, where there are tremendous shifts in physical oceanography, ecology, biogeography, and population genetics. But it is also a puzzling scenario for our tiny barnacle. My interpretation is that we are dealing with the equivalent of two incipient species being formed from one, and it remains to be seen what micromicrohabitat differences they have, but the ‘southern’ one simply doesn’t find that suitable microhabitat to the north of 31°S very often. Our upcoming genomic scan will help point us toward the factors that may be maintaining or promoting this differentiation, similar to John Grahame’s exciting work on intertidal Littorinids.