Research

Field and Stream of Consciousness

24/05/17 10:51

Good morning y'all. What a busy time summer is! Tomorrow I will head out to Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, one of the USG marine labs, to collect some Chthamalus for a project one of my undergraduates (Katie Skoczen) has started. I can't quit you, barnacles! And of course a nice little chance to drop by the beach before Memorial Day weekend too. After that, a short writing retreat and research prep trip to Friday Harbor Laboratories, my touchstone for my entire basis as a marine zoologist. Really looking forward to that!

I mention all this fun and hurry because we ARE all so busy. At some point it just feels good, maybe necessary, to call something "done". So I'm happy to also point to a new PeerJ PrePrint from the lab, work that my other fantastic undergraduate Katelyn Chandler has contributed to.

https://peerj.com/preprints/2990/

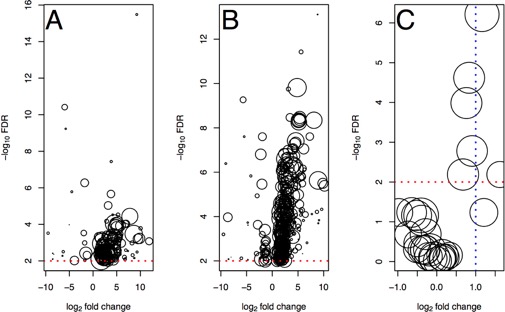

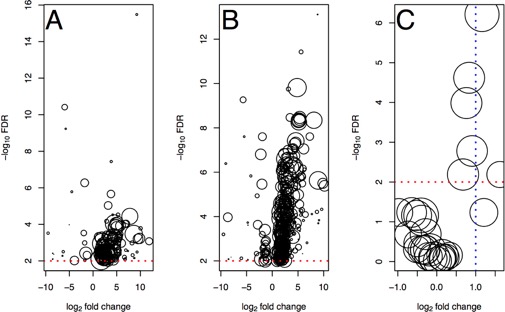

Shown is Figure 3 from this manuscript. We think we are homing in on a story to tell about Pisaster and tolerance to Sea Star Wasting Disease! What this figure shows is changes in expression: individuals carrying the ins mutation on the left in each panel, individuals without on the right. All 3 panels tell the same story: the ins heterozygotes have dramatically lower expression of HUNDREDS of loci than homozygotes do. The first panel is all data; the second panel excludes one individual because it appears to be a funny recombinant (Katelyn's project for this Fall semester); and the third panel is focused on the elongation factor 1-alpha gene. You'll have to read the paper to know why all of this is so interesting!

As with some of my other papers, I have doubts about putting this paper at a "non-impact" journal like PeerJ, one that is focused through peer review on the correct analysis and interpretation rather than whether the story is sexy. Of course I think this story is sexy! But it has already been rejected without review from 2 journals, which reminds me (A) big data is not a big deal in an era of big data, and (B) all of the ego stroking of science often flows through a small handful of gatekeepers and reviewers. They may not be wrong, but lets remember they don't represent the ultimate impact of the science.

That, and the fact that I have very little funding to splurge on many of the more expensive OA journals (did you know Nature Communications costs $5200? Does that seem like those funds could be better used for science in an era of thin funding??? and yet that isn't Nature, it is another journal generated for the hunger of so many scientists needing to publish their work), and that I feel I can get this story out even if name recognition of the cover of the journal isn't as big for some of my colleagues, is why I continue to go with the good publishing experience at PeerJ.

I mention all this fun and hurry because we ARE all so busy. At some point it just feels good, maybe necessary, to call something "done". So I'm happy to also point to a new PeerJ PrePrint from the lab, work that my other fantastic undergraduate Katelyn Chandler has contributed to.

https://peerj.com/preprints/2990/

Shown is Figure 3 from this manuscript. We think we are homing in on a story to tell about Pisaster and tolerance to Sea Star Wasting Disease! What this figure shows is changes in expression: individuals carrying the ins mutation on the left in each panel, individuals without on the right. All 3 panels tell the same story: the ins heterozygotes have dramatically lower expression of HUNDREDS of loci than homozygotes do. The first panel is all data; the second panel excludes one individual because it appears to be a funny recombinant (Katelyn's project for this Fall semester); and the third panel is focused on the elongation factor 1-alpha gene. You'll have to read the paper to know why all of this is so interesting!

As with some of my other papers, I have doubts about putting this paper at a "non-impact" journal like PeerJ, one that is focused through peer review on the correct analysis and interpretation rather than whether the story is sexy. Of course I think this story is sexy! But it has already been rejected without review from 2 journals, which reminds me (A) big data is not a big deal in an era of big data, and (B) all of the ego stroking of science often flows through a small handful of gatekeepers and reviewers. They may not be wrong, but lets remember they don't represent the ultimate impact of the science.

That, and the fact that I have very little funding to splurge on many of the more expensive OA journals (did you know Nature Communications costs $5200? Does that seem like those funds could be better used for science in an era of thin funding??? and yet that isn't Nature, it is another journal generated for the hunger of so many scientists needing to publish their work), and that I feel I can get this story out even if name recognition of the cover of the journal isn't as big for some of my colleagues, is why I continue to go with the good publishing experience at PeerJ.

At what cost?

07/03/17 13:03

So, I've entered a new era. Two of them, in fact. The first: I'm broke, as a scientist. My lab is open, we are collecting (inexpensive) data, we will keep getting papers out. But with very little room for error in budgeting. The second: I've posted my first attempt at "crowdfunding" on Experiment.com. We will see how this goes, as much as anything I'm interested here in juggling my complicated feelings about trying this avenue for supporting my research.

First, what am I asking to fund? About $3000 in additional RNA sequencing for a project in Pisaster that I think will be really of broad interest and will open up our understanding of sea star wasting disease and general responses to pathogens in marine deuterostomes. If you want more of a defense, I encourage you of course to go to the project site at Experiment.com linked above.

Why don't I pay for that myself? Darwin paid for all of his work, right? Well, yes. And I make a good salary. I find this to be a slippery slope problem: if I just admit to not being able to support my work via traditional funding mechanisms, I can pay for some things myself, but with potential costs that exceed their value to my family, and with a potential loss of objectivity that writing proposals, and getting them funded, requires.

We as scientists can't just do whatever we want, in general. We'd like to be doing what will serve our fellow humans and our planet, and to do so effectively means that I won't be plunking down my own money just to know the microbial composition of (for example) soil on a mountain bike trail versus soil that has been undisturbed. Even if it ties together my scientific skills with trail riding, it is such a marginal increase in knowledge (I think) that I recognize that to be folly.

So I am trying this platform in part to find out whether one can appeal to the public and learn about the interest in an idea. The problem of course, is that now - 2017 - everybody I know is stressed by current politics, worried about their financial futures, and already giving money to organizations like the ACLU to help protect those affected by new policies of the new POTUS. So I'm not sure that I will get this funded - and that's OK - but I'm also not sure I will heed that answer.

The other concern with paying for things myself is that it leads to questions of relative merit. If I paid for project X from my own pocket, why won't I pay for project Y? Will I pay for my friend's project, or my student's?

Now, I pay for my smartphone - which is used daily in work-related tasks. I pay for my travel to some conferences, like the Western Society of Naturalists meeting last November. That is not only tax-deductible, it is also an expense I'm willing to bear because it maintains my being part of the science community. My marine science community. So why not pay for polymerase?

I'm not saying I won't some day. There would be freedom in that, to the extent that my family is comfortable with modest expenses. But of course it also gains no traction with colleagues for whom a federal grant, however elusive, is the only currency that can unlock promotion (or perhaps respect). So it is not a good strategy to rely on.

Things are very different from Darwin's day. And his buddies probably privately mocked his barnacle collection. He knew why he was doing it, and that passion and drive is of course one reason many of us are scientists - we really just want the answers to some things. At what cost?

First, what am I asking to fund? About $3000 in additional RNA sequencing for a project in Pisaster that I think will be really of broad interest and will open up our understanding of sea star wasting disease and general responses to pathogens in marine deuterostomes. If you want more of a defense, I encourage you of course to go to the project site at Experiment.com linked above.

Why don't I pay for that myself? Darwin paid for all of his work, right? Well, yes. And I make a good salary. I find this to be a slippery slope problem: if I just admit to not being able to support my work via traditional funding mechanisms, I can pay for some things myself, but with potential costs that exceed their value to my family, and with a potential loss of objectivity that writing proposals, and getting them funded, requires.

We as scientists can't just do whatever we want, in general. We'd like to be doing what will serve our fellow humans and our planet, and to do so effectively means that I won't be plunking down my own money just to know the microbial composition of (for example) soil on a mountain bike trail versus soil that has been undisturbed. Even if it ties together my scientific skills with trail riding, it is such a marginal increase in knowledge (I think) that I recognize that to be folly.

So I am trying this platform in part to find out whether one can appeal to the public and learn about the interest in an idea. The problem of course, is that now - 2017 - everybody I know is stressed by current politics, worried about their financial futures, and already giving money to organizations like the ACLU to help protect those affected by new policies of the new POTUS. So I'm not sure that I will get this funded - and that's OK - but I'm also not sure I will heed that answer.

The other concern with paying for things myself is that it leads to questions of relative merit. If I paid for project X from my own pocket, why won't I pay for project Y? Will I pay for my friend's project, or my student's?

Now, I pay for my smartphone - which is used daily in work-related tasks. I pay for my travel to some conferences, like the Western Society of Naturalists meeting last November. That is not only tax-deductible, it is also an expense I'm willing to bear because it maintains my being part of the science community. My marine science community. So why not pay for polymerase?

I'm not saying I won't some day. There would be freedom in that, to the extent that my family is comfortable with modest expenses. But of course it also gains no traction with colleagues for whom a federal grant, however elusive, is the only currency that can unlock promotion (or perhaps respect). So it is not a good strategy to rely on.

Things are very different from Darwin's day. And his buddies probably privately mocked his barnacle collection. He knew why he was doing it, and that passion and drive is of course one reason many of us are scientists - we really just want the answers to some things. At what cost?

Family Time

17/10/16 12:38

A little over a year ago, I wrote about how hard it is to keep up with life as well as everything we are challenged to do at work. I'm adding to this a bit today; it is hard for all of us. It is doubly hard for those of us raising kids, and I'm going to add - raising a kid with autism. For some it is hard to identify the boundaries of autism, or people have pretty severe preconceptions of what that means. A really inclusive term I've learned lately is "neurodiversity", which really helps us understand all of the interactions we end up having all day, with all sorts of people. But in particular, it reminds us that some folks are exceptionally talented in some elements of cognitive and/or social thought, and others have a mixture of differences in how they perceive sensory or other stimuli. That - to be vague, because otherwise it is personal business - is my son.

I think we take it for granted that faculty, especially junior faculty who are getting themselves known, will travel to give talks at lots of different universities, do fantastic amounts of outreach, as well as establishing top-notch research programs. But those of us considering the efforts of our junior colleagues need to be aware of the toll that going and giving talks has on family life, not to mention requests from our funding agencies to spend a week out of town to serve on funding panels! This work is necessary, and certainly service for our community of science. But, as with most invitations to give a talk at another school, I see that as an unnecessary burden to put on my family. I'm not going to shirk my support of the community, I pretty much never say no to an ad hoc proposal review, and I do plenty of manuscript editing and reviewing as well.

Travel, however, is something we should all be considering carefully in an age in which information can be shared so readily. I fully recognize that nothing yet replaces putting a bunch of colleagues in a room to discuss ongoing collaboration, to meet over shared interests, to consider the merits of a new idea or proposal. But we should find recognizable modes of service and sharing in our community that don't require so much travel, so much time away from home. There are certainly some junior faculty out there whom I've gotten to know their research because of social media; there are others who are great at other forms of sci-comm.

When you can, save the big trips for fun with your family and friends. You'll value that more some day.

I think we take it for granted that faculty, especially junior faculty who are getting themselves known, will travel to give talks at lots of different universities, do fantastic amounts of outreach, as well as establishing top-notch research programs. But those of us considering the efforts of our junior colleagues need to be aware of the toll that going and giving talks has on family life, not to mention requests from our funding agencies to spend a week out of town to serve on funding panels! This work is necessary, and certainly service for our community of science. But, as with most invitations to give a talk at another school, I see that as an unnecessary burden to put on my family. I'm not going to shirk my support of the community, I pretty much never say no to an ad hoc proposal review, and I do plenty of manuscript editing and reviewing as well.

Travel, however, is something we should all be considering carefully in an age in which information can be shared so readily. I fully recognize that nothing yet replaces putting a bunch of colleagues in a room to discuss ongoing collaboration, to meet over shared interests, to consider the merits of a new idea or proposal. But we should find recognizable modes of service and sharing in our community that don't require so much travel, so much time away from home. There are certainly some junior faculty out there whom I've gotten to know their research because of social media; there are others who are great at other forms of sci-comm.

When you can, save the big trips for fun with your family and friends. You'll value that more some day.

Backlog Manifesto

05/07/15 13:25

small brazing project, JPW, 2011.

Summer is a time to gain perspective, at least in the academic world where we are fortunate to have a break from teaching and committee work (or at least, less of it). For many of us, this is a time for field work and travel to conferences, a time to catch up on the writing and analysis that was put off by the pressures of teaching. It's also when we make good on a lot of promises to kids, to family, to ourselves.

I just took my first real vacation in a long time. It was unrelated to work, unrelated to research. I did as little email-checking as I needed to, though there were a few tasks to keep juggling. And it is probably really trite to come back from vacation with a clarity that "life should be more like this", but there you have it.

I have been faculty for 10 years. I've literally lost count of how many PhDs, masters, and undergrad students I have shepherded through the process of research, how many different classes I have taught, even how many of my colleagues I was on committee to hire. I'm one of the semi-old guys now. I've had plenty of funding for my research, published a lot of it. I've been graduate coordinator for 4 years, and let me tell you that is both thankless and rewarding at the same time.

What concerns me about the academic life is the pressure to keep it up, to go more and more and more. Some of this is self-inflicted, of course, but we all know the numbers games that our university administrators are running, as well. For me, this has led to a lifestyle of juggling so many different projects that I recognize fully how each is being short-changed, and the people on them as well.

When I commit to a graduate committee, or to a student being in my lab, I should be committing sufficient time to that person that they will truly gain from the interaction – not that they will have to squeeze in a few half-baked moments with me when I spend half the time recuperating my understanding of what they are doing because it has been a few weeks since we discussed it and I've had to change mental focus so many times and haven't slept well and, and, and. Period. And I worry that isn't happening.

I'm not able to read much these days; I glean. I use close to a month of work hours to being grad coordinator, probably another month to basic administration of the lab (ordering, repairing, etc.) itself, and that is not at all dismissing the work my grads put in to the same tasks. I throw myself into teaching, and have been shuffled to new teaching assignments often enough that nothing is in balance (at least it isn’t getting stale!). And most importantly, I'm having a hard time finishing what I started because I feel the pressure to start something new. This is what I'm about to tell you, needs to stop.

So, though I am on about 3 pending proposals, and associated intellectually with a couple more, I am not submitting any more this year. Or maybe next. Funding is a precious commodity for research. My effort now is not scratching my head for ideas that might be fundable, to keep the treadmill at full speed, but to focus on the ongoing work and let it identify for me what ideas need to be funded, and how. What ideas arise organically, are useful, are critical to pursue? What are the priorities? Our planet, biodiversity, public health, as well as knowledge; each of us would come up with a different list of course.

I am helping 2 students finish their PhDs, and another 6 (unless I’ve forgotten somebody, which wouldn’t be surprising) that I'm currently on their graduate committees (in the past I have been on many more at once). That feels like enough, knowing all it takes in the last push. Including those who have recently finished - a masters student, postdocs, colleagues from other labs - I have at least 20, probably many more, manuscripts that are all in various stages of being written or generated. That is enough to keep me busy for years in and of itself! I want to do this science right, to do it the best possible way, rather than frantically pushing it away to get to the next thing. The people involved deserve my attention.

Notice how committee and commitment are related...?

This also means that travel is something that I am limiting. Travel is one of the true perks of a biologist, and I have excellent and dear colleagues all over the planet at this point. I get invited for talks, I get invited for intense one-on-ones about research or collaboration, and of course there are intriguing conferences where you get the opportunity to see more of the same people but in new! exciting! places where you still drink at the bar across the street from the conference center.... and I have to say no most of the time. If I have told you “no” recently, you aren’t alone. The environmental costs of flying are high, and this is a true priority to consider. The time (and financial) costs of travel are high as well, and I have to prioritize which ones are possible in the scope of all else I do professionally and personally. I think I would be interested to see how extended teleconferencing (Google hangouts, Skype, FaceTime, etc.) could replace some of these interactions – sure, you miss the local cuisine and some beers, and some research interactions are minimized – but we shouldn't neglect this magic that has transformed our professional lives in recent years, either.

This is a long justification for why you will hear "No" from me more often than in the past. I’m not doing anything other than recognizing my career as a long-distance run rather than a sprint, I’m trying to do right by those whom I am already committed to helping, I'm trying to do justice to the science I've already committed to, and I'm trying to do what is best for my family and personal needs as well. And I promise – and some of you know I’ve been up front about this in recent requests to come give a seminar, etc. – I won’t be offended if you tell me “No” as well.